Plotting press coverage when every story is political

For public affairs professionals, the challenge of comms is no longer just about getting a message through. It’s about managing how that message evolves once it enters the current fast-moving, politically-charged, and increasingly fragmented media landscape.

The latest report from Vuelio, ‘How news travels in today’s fragmented media environment’, provides a data-driven look at how stories move across the modern ecosystem — here is a closer look at what this means for those operating at the intersection of politics, policy, and public opinion.

A media ecosystem without clear borders

Tracking specific stories through the media confirms what those in Westminster and Whitehall already know: there is no longer a single, stable route for a story to reach its audience. Instead, the news cycle has become an ecosystem – complex, reactive, and full of feedback loops between political actors, journalists, and the public.

In this ecosystem, narratives that once followed predictable arcs (a ministerial statement, a round of coverage, then commentary and response) now move multi-directionally. They emerge from local conversations, ricochet through social feeds, and land on front pages already laden with political significance.

Mental Health Matters’ External Affairs and Policy Manager Charlie Campion sees the closer connections playing out, directly impacting how PA and comms teams work:

‘Politicians are paying closer attention than ever to public opinion. That means that conversations in the press, online forums, and across social media have become essential to any successful public affairs strategy and to influencing the government’s agenda. This is why integration and collaboration between public affairs and communications teams is more critical than ever.’

Political buffers and public pinball

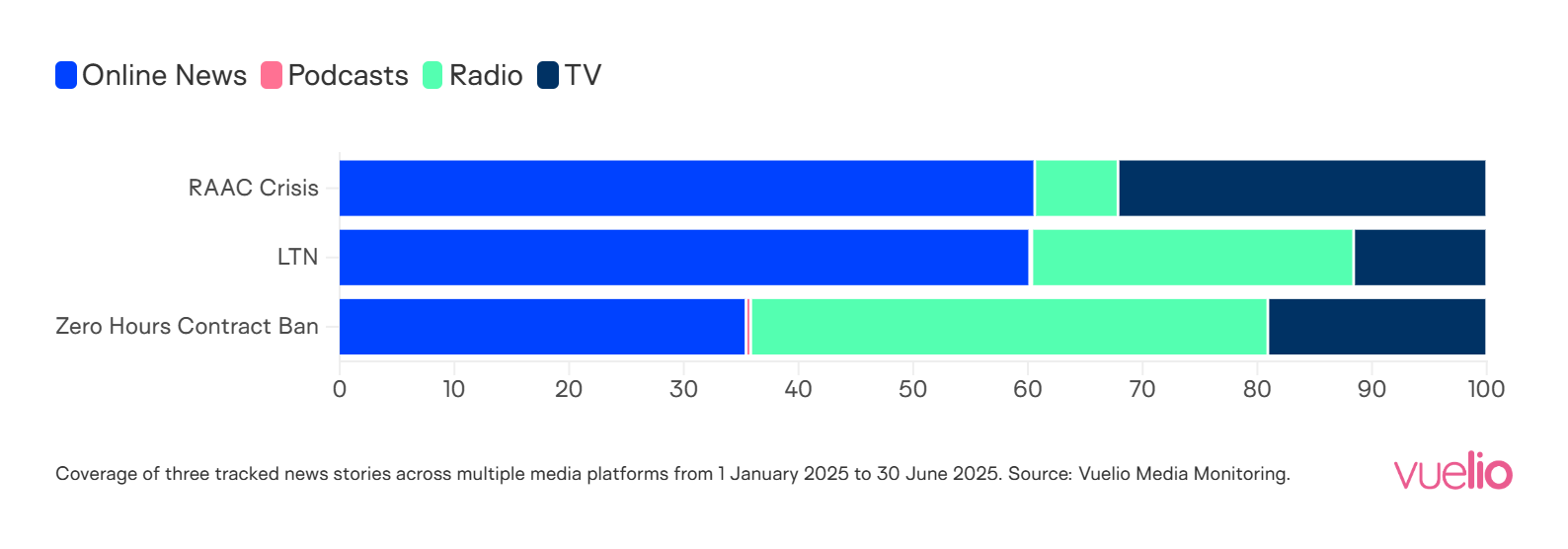

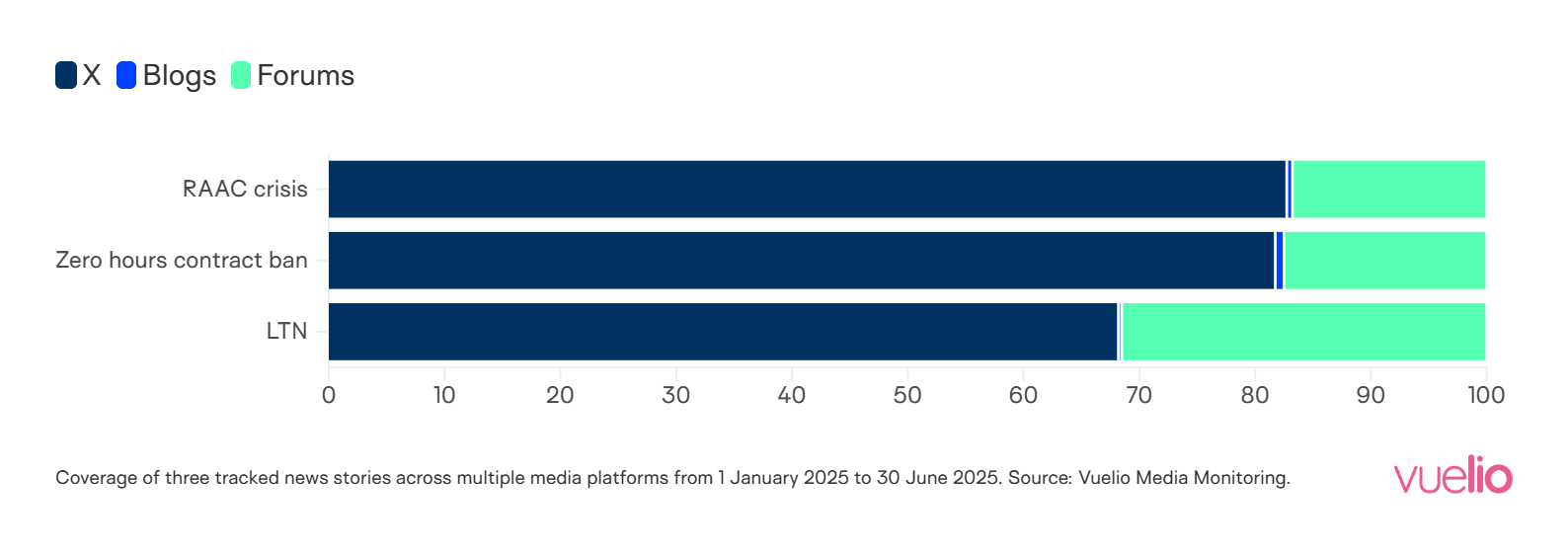

Vuelio’s analysis of five major stories from the first half of 2025 spotlight this effect. From reporting around the RAAC Crisis to Low Traffic Neighbourhoods and the Zero Hour Contract Ban, each issue demonstrates how the political sphere can act both as amplifier and accelerator.

Low Traffic Neighbourhoods (LTNs) began as a hyper-local debate about planning and mobility. But as online community discussions grew across X, Reddit, and local blogs the topic was pulled into the national conversation. By the time of local elections, it had become shorthand for wider political divisions around environmental policy, civic freedom, and government control.

RAAC Crisis reporting by contrast, shows how policy accountability narratives spread in unexpected ways. Regional news outlets drove much of the early coverage, but attention from MPs and regulators kept it alive in the national press. The story’s longevity wasn’t purely due to public interest — it was fuelled by parliamentary intervention and the policy implications that followed.

The Zero Hour Contract Ban demonstrated the convergence of social and political storytelling. What started as personal testimonies across social media grew into union advocacy and, eventually, coverage of specific political action, including the Worker’s Rights Bill.

Each case underlines a central point: policy stories don’t just sit within political news anymore. They move between issue communities, partisan echo chambers, and mainstream media with remarkable fluidity – reshaped every time they cross a new threshold.

Kelly Scott, VP Government & Stakeholder at Vuelio, summarises the phenomena:

‘The journey of public interest stories can be like a pinball machine — hitting political buffers that change their course. It’s vital to correct misinformation at pace, engage with both media and political influencers, and mobilise credible third-party voices.’

In this ‘pinball’ model, the risk of distortion is constant — but so is the opportunity for those who can anticipate the next pivot.

Fragmentation and connection

Major obstacles for any comms team tasked with getting vital information out to audiences are media siloes, which are abundant, even in an age of digital abundance. Reporting and conversation around the story of Surge Pricing for example, shows different media audiences consuming parallel (but largely disconnected) versions of the same issue.

Broadsheets and business outlets framed surge pricing as a question of market regulation and fairness. Tabloids focused on its impact on consumers, from concert tickets to the price of a pint. Each narrative reinforced itself within its own echo chamber, while cross-over between the two remained minimal.

This division presents a serious challenge for public affairs teams: a single policy debate can now exist in multiple, self-contained forms. A story that looks resolved in one arena may still be live (and inflamed) in another.

National broadcasters remain one of the few connecting threads, offering brief bursts of shared attention, but even these tend to lack the interpretive depth audiences once found in print. Increasingly, it falls to issue specialists, from think tanks to influencers to community groups, to bridge the gaps.

The collapse of siloes between media and politics

Perhaps the most consequential finding for political communicators is how blurred the lines have become between media management, public affairs, and reputation strategy.

In a world where journalists quote MPs’ tweets and policy conversations trend before they’re debated in Parliament, separating media and stakeholder engagement strategies could be dangerous.

‘In our recent call for increased investment in the charity sector ahead of the Autumn Statement, our approach extended beyond engaging MPs or the Chancellor directly,’ says Charlie. ‘The Mental Health Matters team worked with the media and in turn, built public support that can drive change.’

For public affairs professionals, integration is now essential. Understanding the media’s rhythms helps shape political engagement, while political intelligence helps anticipate where and how a story might evolve once it enters the news cycle.

Influence in an age of flux

Public affairs practitioners must think beyond Westminster and mainstream media to include the new spaces where policy conversations take shape — podcasts, Substacks, TikTok explainers, and influencer commentary all play a role in framing political stances and, in some cases, impact policy.

If the traditional model of influence was about control, be it controlling the message, the moment, and/or the medium, the new model is about navigation.

‘Know where your audience consumes content, and meet them there’ – Burson’s Head of Media Relations Strategy Sean Allen-Moy.

Fragmentation hasn’t diminished the power of public affairs; it’s simply expanded the field. Every story, from infrastructure to employment, is now a live and dynamic object — interpreted, politicised, and repurposed across audiences.

Those who can read the ecosystem, engage multiple stakeholders, and adapt their strategy in real time will not only survive this shift but thrive within it.

Because in today’s media environment no story stays still, and no issue stays purely political.

Read our full report ‘How news travels in today’s fragmented media environment’ and find out more about Vuelio’s services and support for the Public Sector here.

Leave a Comment