‘We’re living in an utterly abnormal political era’: Governmental communications in 2026

Political comms reflect the current chaos of the political climate. To help make sense of the uncertainty, Vuelio partnered with the Institute for Government alongside former No. 10 Press Secretary and The Rest is Politics Presenter Alastair Campbell, The Times Washington Editor Katy Balls, Chief Executive of Government Communications (2021 – 25) Simon Baugh, Institute for Government Programme Director Alex Thomas and Senior Fellow and moderator Jill Rutter for the webinar ‘The Trump challenge: Chaos, confusion and government communications’.

Featuring research conducted by the Vuelio Insights team, the panel considered whether traditional functions of accountability still work, how battles for attention will play out in the UK political space, and how the comms industry can adapt accordingly.

‘We’re not living in normal political times,’ warned Alastair Campbell. ‘But most of the media and political establishment are still acting as though we are.’

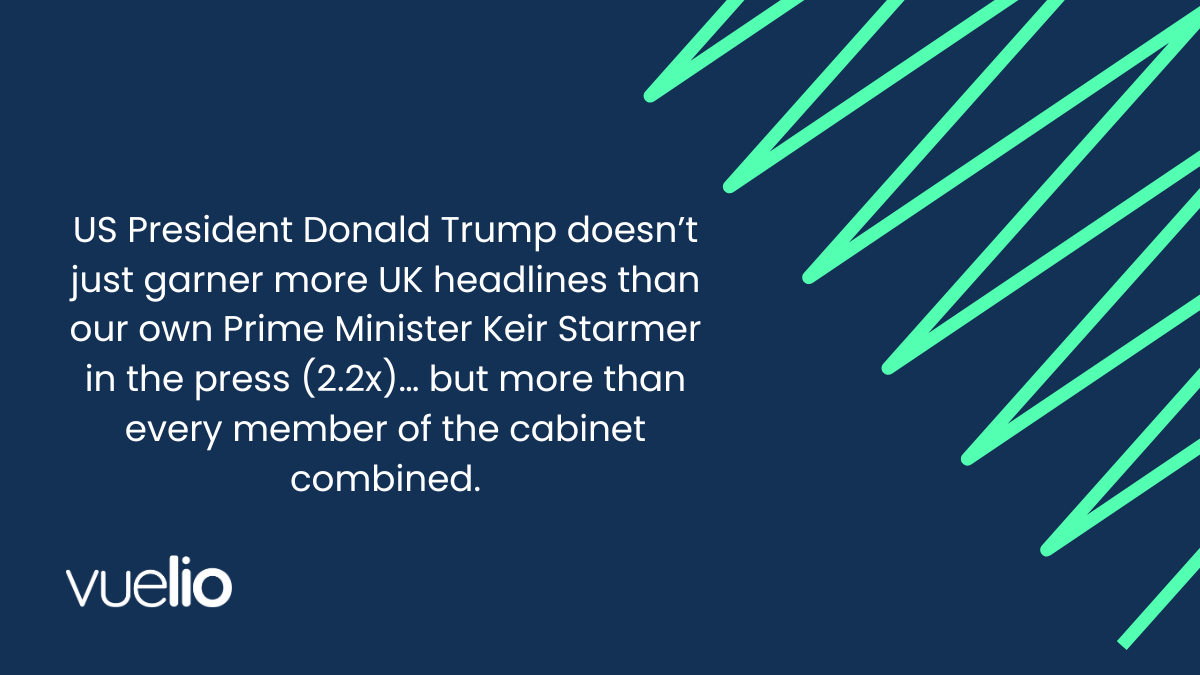

Where is the UK press centring its political reporting? One guess…

A startling statistic from Vuelio Insights shared during the webinar was that US President Donald Trump doesn’t just garner more UK headlines than our own Prime Minister Keir Starmer in the press (2.2x)… but more than every member of the cabinet combined.

What is coming over from the US is ‘rewriting the comms playbook’ was moderator Jill Rutter’s summary of the situation, but what are the lessons for UK comms people tasked with communicating in this climate?

‘This is a reverse of the overscripted, cautious minister or shadow minister, refusing to deviate from their lines to take,’ said Rutter. ‘While Trump plays fast and loose with the truth – he insults reporters, particularly women, and news outlets he does not like who dare to ask critical questions – he seems to have found a way of communicating that mobilises his supporters while enraging or frustrating his opponents, achieving the twin gods of authenticity and cutthroat.

‘Trump’s social posts are miles away from Keir Starmer’s careful Substack and TikTok updates. Is this what good modern political communication looks like?’

Political reporting has changed – and comms needs to catch up

Campbell had other stark warnings for those waiting for official organisations to step in with regulation, and reason, in the face of obfuscation:

‘Institutions that we expect to uphold standards in public life, not just the media, are just not functioning.

‘There is this totally new landscape which is transforming all of our lives in terms of how we try to make sense of what’s happening politically.

‘We have to stand back and apply a little bit of judgment as to what is actually news – maybe take some of the more “old-fashioned” disciplines of journalism from the print side of journalism into the broadcast media space.’

The importance of access and availability for the press

Regularly reporting from Washington, Katy Balls highlighted how vital ready-to-use quotes are from political figures for journalists – particularly in this 24/7 news cycle, even when they are controversial:

‘In one way, Trump is easy to cover because he is everywhere, all the time – you’re not having to haggle for too much access. He is speaking all day to the press. In terms of access and visibility, and the number of questions this White House tends to take, it’s extensive when you compare it to the UK and Europe.

‘Of course, where it gets more complicated is how adversarial it is…’

The fragmentation of the media has changed how a political story travels

Another challenge to contend with is what happens to updates from government figures once they’ve been reported by the media, according to IFG’s Programme Director Alex Thomas:

‘There’s a lot about this that is not new – the world has seen unpredictable, charismatic, authoritarian populists before. If you’re prepared to bend or ignore the truth, it’s actually quite easy to grab attention.

‘For all that Trump is a novel force, information fragmentation and social media means that this is different.’

From the journalistic point-on-view, Balls highlighted the impact of ‘new’ media in how stories are shared, and reshaped, as they travel to their audiences:

‘America is ahead of the UK in terms of how it uses it at the moment. When you look at the last US election, there was a podcast strategy to reach the young men who were perhaps less good at getting out to vote, a bit non-political. Unconventional ways to get to voters – it didn’t feel as though it came up through focus groups – it feels like an authentic conversation.

‘The traditional means of page adverts, TV – social media is one of the reasons that is a weaker thing now. There’s a feeling in American politics at the moment that if you have an authentic message, it will travel because people will share it.

‘I don’t think we’ve quite yet had a TikTok election in the UK, but certainly if you look at Nigel Farage and Reform UK – the parties that get ahead of this are the ones that are going to be able to unlock some of these votes that have been notoriously tricky to get for certain parties.’

Campbell concurred on which UK parties are utilising TikTok to mobilise potential voters: ‘I don’t know if it’s still the case, but certainly the last time I checked, Nigel Farage has more TikTok followers than every other MP combined. They have worked on this for years.’

Speaking out to be heard

Campbell reiterated the importance of speaking out to connect with audiences:

‘Starmer should be out there, he should be on every platform, all the time, and his team should be building the content that allows him to do that. I do think you have to wake up every day and say “how do I explode into the attention economy today?”. Because that’s what we’re in now.

‘I hope that the podcast world is part of a desire for a kind of deeper debate. It’s part of this completely transformed landscape where you have to be heard. Connection is happening all the time. Now, that doesn’t mean you should be communicating all the time. You should be thinking about how your message is being communicated.’

Are tried and tested comms strategies still useful?

On whether the growing influence of ‘new’ media means the end of the traditional comms handbook, Chief Executive of Government Communiations (2021 – 25) Simon Baugh saw a need for evolution and expansion, not abandonment:

‘When people are talking about social media, they over-focus on the tactics and this sense of chaos. What they should really be thinking of is more that this is kind of the modern day equivalent of Franklin Roosevelt’s fireside chats. How do you have a direct conversation with different audiences who are operating within their own fragmented bubble?

‘You’ve got to be kind of thinking every day, how am I going to create attention, how am I going to create a story? Though, what I think people often miss is that you need to have a story to tell.

‘And I think if you asked anyone in the UK, what does Trump stand for? They would be able to tell you. I think if you asked people today, what does Starmer stand for? I think they would struggle to give you an answer.

‘I actually think if you asked the cabinet, you’d probably get different answers as to what the driving purpose of this government is. When MPs talk about improving government communications or needing to get its message across, it suggests there’s a coherent message to communicate. I think the real issue with the government’s communications has not been a lack of ideas or even technical proficiency, but a real lack of strategic purpose.

‘The most important lesson is not to mimic the chaos, but to really mimic and master the strategic focus.’

Putting a premium on truth

‘We’re in a post-truth age,’ said Campbell on the damage of disinformation.

‘Many politicians who are thriving across the world – Trump, Putin, Modi, Erdoğan – have a pretty tenuous hold on truth and they don’t get called out for it. With our desire for strengthened ministerial codes, what we feel probably is that ultimately politicians don’t like lying, don’t like bullying and intimidation – that’s my experience. In most of our democracies, it has meant political death.

‘We need to fight harder for politicians, however imperfect they may be, who at least keep striving to understand that fact as the center of debate is incredibly important.’

Thomas advocated for a recentring of the importance of truth in communications:

‘Can we create a world where there is a premium on fact and seriousness among ever increasing amounts of AI slop? Does proper communications, proper reporting, authoritative reporting become a kind of premium product?’

Baugh also advocated for transparency in messaging:

‘I do wonder whether there is a point, perhaps we haven’t reached it yet, where radical transparency and openness about the choices and trade-offs that come with delivering what the public want would be an effective political tactic.’

A better form of politics

For political communicators, ‘it’s tough at the moment,’ Campbell acknowledged.

‘You know, you wake up, you turn on the telly or the radio, you read that paper, everything’s pretty depressing. I get hope from the fact that so many people know how bad it is. When I go into schools and colleges and stuff, there is a sense that people know this is unsustainable.

‘People really want change, and it is up to a generation of politicians to come through and lead that change.

‘But it’s not just about the politicians. All of us can make the change. All of us can actually argue for a better form of politics.’

Watch the full Institute for Government and Vuelio webinar here, and find out more about the impact of media fragmentation by downloading the Vuelio white paper ‘How news travels in today’s fragmented media environment’.

Leave a Comment